Communicating direction

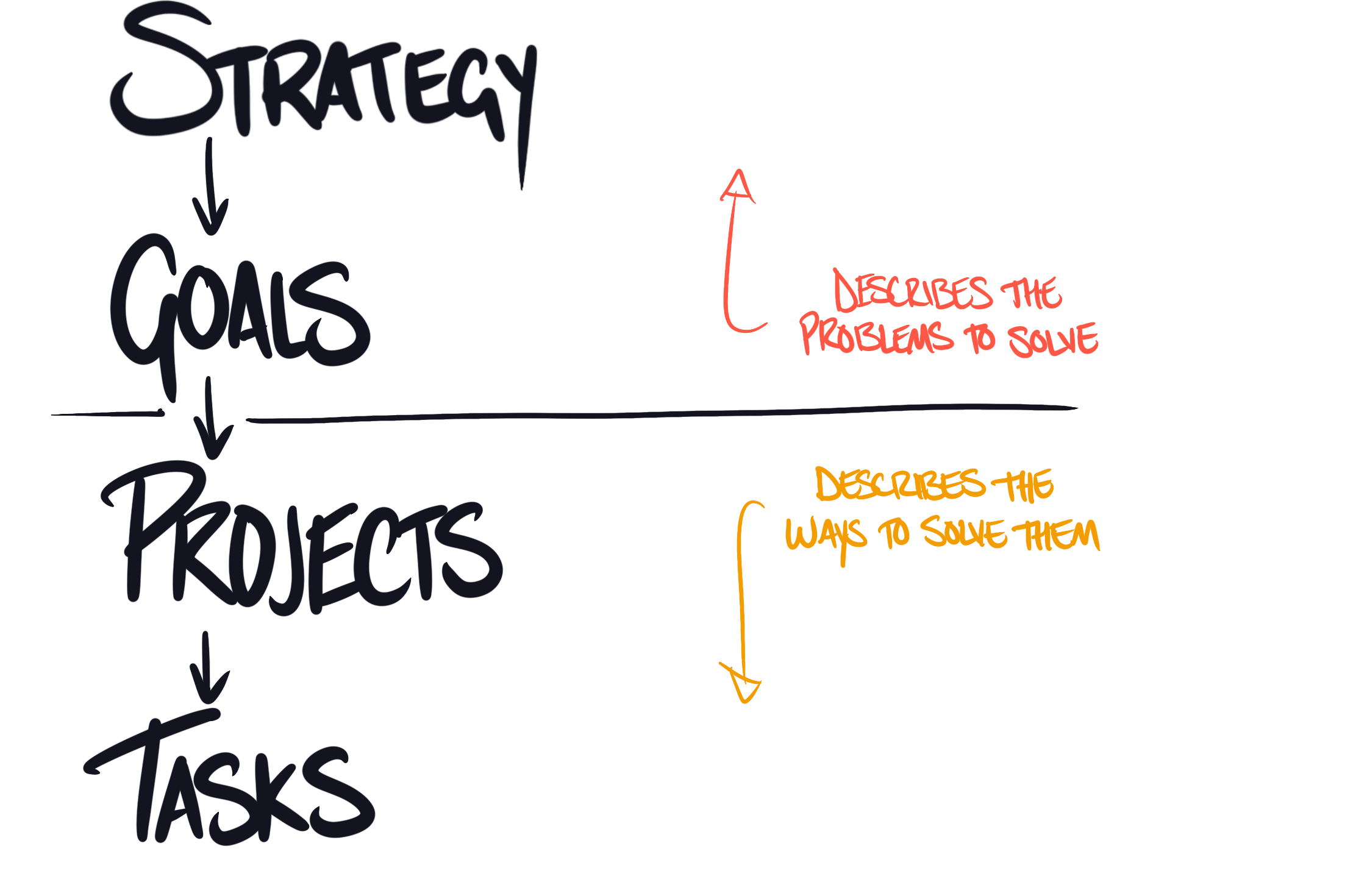

Setting direction is an essential muscle for every organization. And no matter how you divide it up or what you call the pieces, that direction always takes four forms.

Strategy: “A computer on every desk and in every home.”

Strategy is the kind of direction that looks great on a slide. Strategies tend to use a lot of words like “revolutionize”, “transform”, and “reinvent.” That level of communication helps teams understand where they’re going. But it’s terrible at showing them how they can get there.

Goal: “Increase the number of computers in schools by 20% over the next two years.”

Goals break down the big problems that stand in the way of achieving a Strategy. They capture the next few steps that you need to take. Goals outline specific problems to solve — not the ideas you have for solving them.

Project: “Start a new education-focused marketing campaign.”

After Goals, we have Projects — the actual work that you’ll do. There are many possible ways to achieve a goal. Project-level communication is all about sharing the approach you’ll try.

Task: “Call Jimmy in Marketing”

Tasks are the atomic bits of work that go into making a Project happen. They can also be called stories, action items, or any number of other labels.

There are many ways to share each type of direction information. OKRs are one of the more popular ones. But a way that works well for one information type won’t work well for another.

Just like water is wet, OKRs are problem-focused, time-bound, and measurable. Using OKRs to share information which does not share those characteristics goes against their nature and won’t work well. They’re only good at sharing information which is also problem-focused, time-bound, and measurable.

They aren’t a good way to communicate Strategy. They aren’t a good way to track the Projects that you’re working on or the Tasks that make them up.

OKRs communicate Goals.

Why and how OKRs work

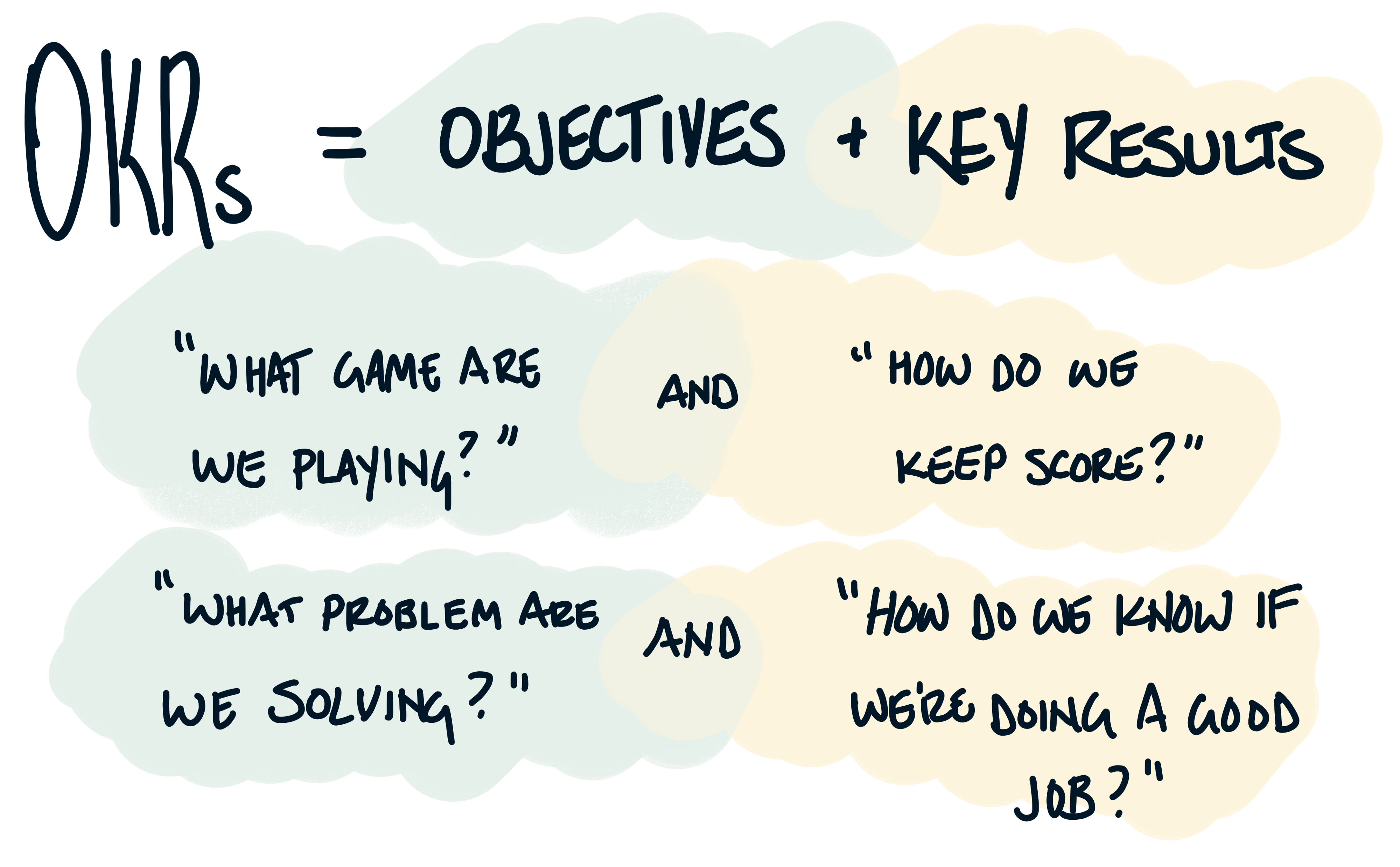

OKRs stand for Objectives and Key Results.

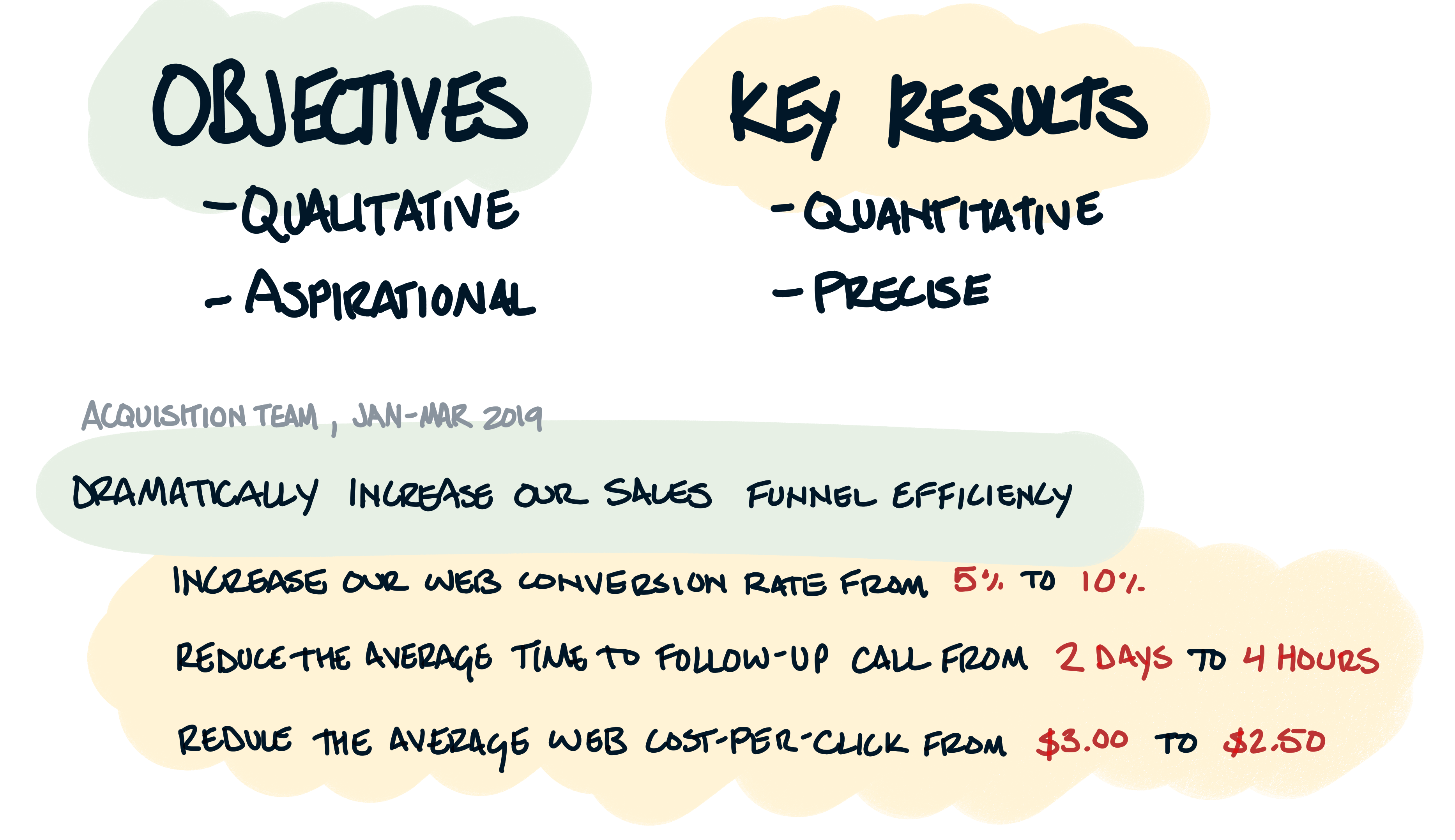

Objectives define what you’re trying to accomplish. Key Results measure if you’re succeeding. Objectives are best when they’re qualitative. Key Results are best when they’re quantitative. Here’s an example of a good OKR.

This OKR works for a few reasons.

First, the Objective uses simple language to focus on a clear problem. It’s qualitative, aspirational, and easy to understand even if you have very little context. But, the Objective alone leaves some questions unanswered. What part of the sales funnel will you focus on? What do you mean by dramatic? How do you define efficiency? Answering those questions is where the Key Results come in.

The Key Results fill in the edges of the OKR. They give extra context and define a finish line so that you know when you’re done. They’re quantitative, verifiable, and precise.

Second, this OKR works because it’s cross-functional. Almost none of our work happens in isolation. A goal like improving sales funnel efficiency isn’t the responsibility of a single group. It takes a village. Marketing may have to create new materials. Engineering may need to work on page load time or update some back-of-house tools. Sales may need to kick off a round of internal training or rethink how they manage existing accounts. Achieving big goals is a team sport. Having one set of cross-functional OKRs aligns everyone, no matter their role, with something to work towards.

Third, this OKR works because it’s time-bound. Having an end date forces you to find a piece of the problem that can be solved right now. Not eventually. Not on a 3—5 year horizon. Right now. It forces you to ask: “What’s the three-month version of this idea?” When the time period ends, you will have made measurable progress towards your Strategy.

Using OKRs at scale

Hierarchy

Adapted from the fine folks at GitLab

All OKRs follow the same pattern. That pattern works well with organizations big and small and at levels high and low. They’re useful for big company leadership teams and for tiny startups. But OKRs don’t really start to shine until you stitch multiple layers of them together.

OKRs are hierarchical.

Company-wide OKRs give the company its strategy. Department-level OKRs refine the company-wide set into more focused chunks. And team-level OKRs slice off manageable pieces of the problem to solve one by one.

If you do it right, there’s a clear connection from every OKR back up to the OKRs above it. In that structure, OKRs become a powerful tool for creating organizational alignment. They help every person understand why their work matters and how it relates to the whole.

It’s tempting to think of lower-level OKRs as a subset of the OKRs above them. And to some degree, that’s true. Lower-level goals should echo higher-level goals. But if that coupling is too tight — if every set of OKRs fits neatly into the set above with no overflow and no gaps — then you miss out on a set of massive benefits.

It’s much better to have a portfolio of OKRs that loosely align. They shouldn’t all point in exactly the same direction. Some OKRs in the org may be slightly out of bounds relative to the ones above them. Some higher-level OKRs may not be fully supported by the OKRs below them. That minor misalignment may feel like a mistake but it’s actually a powerful benefit.

When building an earthquake-resistant house, there are lots of little gaps where things don’t quite line up. In the short term, that seems inefficient. But when the ground starts shaking, those gaps let the building sway back and forth. It absorbs the shock that would break a ‘better constructed’ building. Those small inefficiencies become a source of strength.

Similarly, keeping OKR levels loosely aligned instead of rigidly stacked gives teams flexibility and resiliency. By expanding their OKRs, they can stretch slightly outside of the problem space of the set above them. And by leaving a gap, they can highlight where a parent goal is unlikely to succeed.

OKRs should align, not stack.

Self-determination

Setting OKRs is always a two-way conversation.

Leaders set high-level OKRs and share them with their teams. Then teams set their own OKRs and share them with their leaders.

In most cases, the higher and lower-level scopes line up well but every once in a while there can be a mismatch. Sometimes a team doesn’t have the resources they need to achieve a higher-level objective. Sometimes the reverse happens and a team thinks the parent goal isn’t ambitious enough! Keeping the conversations two-way makes space for those differences to bubble up.

It can be tempting for leaders to bypass the back and forth and dictate OKRs to the teams below them. It feels more efficient in the short run but this is a big mistake!

Lower level teams have more context. Generally, they will have better ideas on how to solve the problems that your OKRs represent. Leaders set OKRs for their teams directly handicap their teams from finding better solutions. It diminishes and disempowers them. Not only does the quality of decisions suffer, but the leader becomes a bottleneck. Every decision or change in direction is something they have to oversee and approve personally.

Be generous with your feedback but let teams make the final OKR decisions themselves.

Great Expectations

OKRs should be difficult, not impossible.

Teams should set their OKRs slightly beyond what they think they can deliver. That slight overestimation keeps prioritization sharp and goals lofty. That pressure is helpful but it has a consequence worth mentioning.

If everything is working well and teams are setting bold goals, then they will likely only achieve around 70% of them. That’s okay!

Unlike other goal setting methods, a minor failure rate is actually a sign that things are going well. It means teams are trying to stretch themselves to slightly beyond the edge of their capabilities.

If a team only achieves 30% of their OKRs then that’s feedback that their goals were too aggressive. If a team achieves 100% of their OKRs then it’s feedback that they can set more aspirational goals next cycle. Neither result means a team did “well” or did “poorly”. OKRs are not a tool to judge the quality of a team’s work. They exist for feasibility feedback, alignment, and transparency.

Regular Review

Leaders have two tools to help maintain the right balance of OKR difficulty.

They can adjust how often they review results. And they can choose whether to include OKRs in performance management.

Deciding how often to review OKR results may take some experimentation. Review them too often and nothing will have changed. Review them too rarely and by the time you realize a problem has cropped up, it will be too late to help. The ideal timing is debatable but having a regular review process is not. Routine check-ins discourage teams from setting their goals too high. Having to tell your leaders over and over again that you’re nowhere close to delivering isn’t a situation that anyone enjoys. After having that experience once or twice, people will set more achievable goals in the future.

The second tool leaders have to balance OKR difficulty isn’t really a tool at all. It’s more like a gigantic red DO NOT PRESS button.

Never tie OKRs to promotion or compensation.

Performance management and OKRs must be completely separate from each other. Blending the two encourages teams to sandbag their goals. If they set laughably easy goals and surpass them, they’ll look great and get a nice big bonus. If they set bold goals that they won’t always achieve, they’ll get nothing. The people who habitually aim low will be rewarded and the people who set ambitious goals will be penalized.

Using OKRs for performance management triggers a downward spiral. It’s very difficult for organizations to un-learn that politics is more important than progress. That’s not a place that any leader wants their company to be. Keeping OKRs separate from performance removes the incentive to sandbag and encourages teams to aim high.

Together, regular reviews and separate performance management routines help keep OKRs where they belong --- difficult, but not impossible.